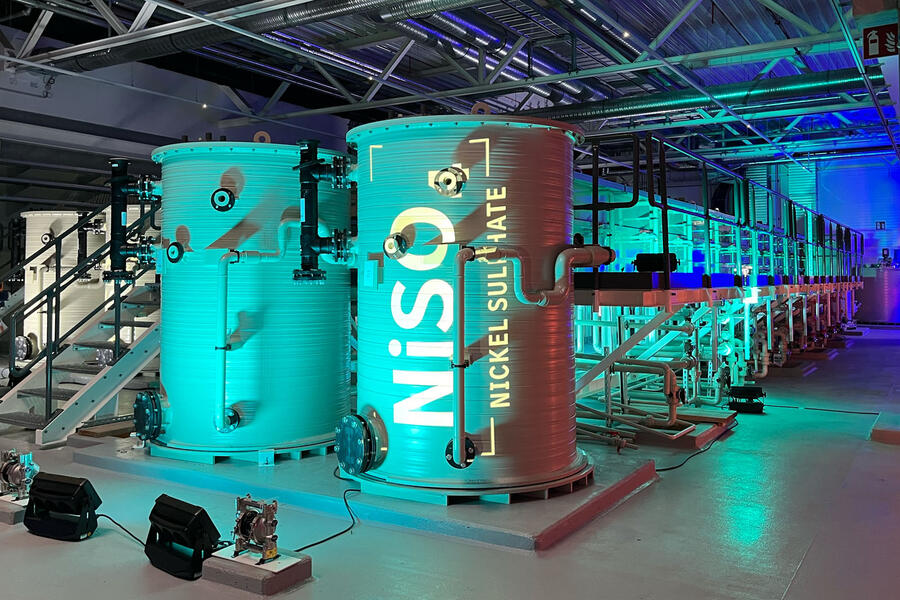

Finally, it is treated with sulphuric acid, ammonia and an organic solvent, producing sulphates of copper, cobalt, manganese, nickel and lithium.

The copper, manganese and lithium are stored as liquids in huge drums, whereas the cobalt and nickel are crystallised before being recovered and re-used.

It will take around “three to four years” to hit the 2500-tonne annual yield, said Burzer. This is because there is currently a limited stock of end-of-life lithium-ion batteries, owing to the relative newness of Mercedes’ EVs. Its first mass-produced electric car, the EQC, was launched in 2018.

Burzer said: “You have to have a certain amount of batteries in the market before you can [start to] recycle them. So first you have to produce them, and this will be with raw material coming from mines, because you don’t have anything to recycle.“Our quality standard for our batteries is eight to 10 years, so there will be some delay. That means that for the next three, four or five years it works [at a lower capacity], but in parallel what is very important is that we understand the process and, more importantly, we understand the scalability.”

In the meantime, Kuppenheim will recycle batteries from Mercedes’ research and development efforts, as well as from prototype cars. Burzer said Mercedes is also open to taking in other manufacturers’ batteries, as well as looking at different chemistries.

“LFP [lithium iron phosphate] and NMC [nickel manganese cobalt] together, we could do that,” he said. “The question is: do you do them in batches or not? We have to think about efficiency.”