July began at home in Montreal, where as it was very hot and we were having work done that meant keeping the windows at the front closed, I spent a lot of time sitting on the back balcony reading. Then on the 21st I flew to Florence, where I have been ever since. I read 23 books, and some of them are sufficiently predictable that people guessed in last month’s comments that I was likely to read them, and others are perhaps less obvious.

Invitation to Italy — Victoria Springfield (2024) Romance novel set in Italy. A single mother goes to Italy after her divorced husband takes their daughter there for the summer. The mother finds a new romance and also peace with her ex and his new partner. The love interest is the least interesting character—the protagonist, her daughter, and her best friend, are great, and so is the old lady who runs the hotel, who has her own new love and closure on her past. There are way too many Big Misunderstandings here, but the descriptions of the island of Procida are terrific. (I only ever saw Procida from the boat on the way to Ischia, but I was convinced.) Springfield seems to specialise in these plots connected by place and entwined over time.

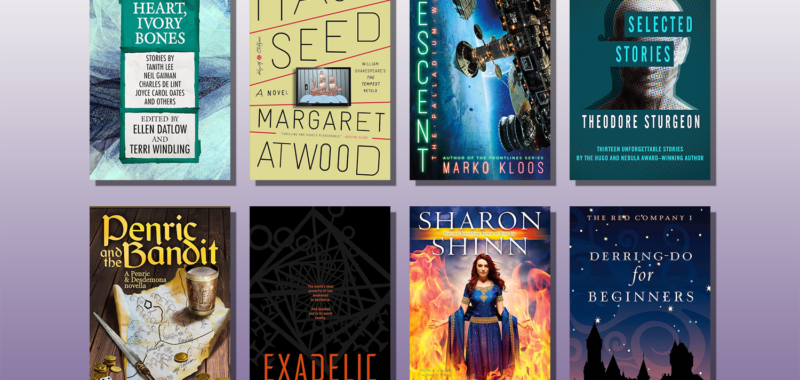

Jeweled Fire — Sharon Shinn (2015) Book 3 of Elemental Blessings. Corene, who has been a minor character in the earlier books, takes centre stage here as she voyages to another kingdom and has to negotiate different customs and etiquette while solving a mystery and discovering herself and who and what she cares about. I think this would work just fine as a standalone book, so you could start here if it’s what happened to be around, though I am enjoying reading them in order. Shinn’s worldbuilding feels absolutely solid, and her prose here is a joy to read. I love these, and I wish they’d had more attention when they came out. These are kingdom-scale books, with nifty metaphysics.

The Boxcar Children — Gertrude Chandler Warner (1924) Some orphans run away to manage on their own in the wonderful free America before the Great Depression, where a boy can get a summer-type job helping in a garden and support his three siblings, who are living in an abandoned boxcar. The joy of this kind of book is the contrivance, specifically the details of the way the children contrive to live and have fun. Before anything worrying happens—cold weather, truant officers—they are rescued by a rich and loving grandfather. Of course they are, that’s the kind of book this is. I’d have loved this as a child, but I did not run across it until now. I found it a fast, fun read a hundred years later and can see how this is a beloved classic.

Exadelic — Jon Evans (2023) Re-read, book club. This is a book that does not cease to surprise, even on a re-read. It made a terrific book club book, as everyone had such interesting things to say about it. It’s a fast-moving science fiction novel about the nature of the world and reality, with unputdownable pacing. I mentioned on my earlier reading of it how much fun it is and how much I enjoyed the successive layers of revelation. The most surprising thing that came up in book club was that Jon had not consciously intended the cave imagery that runs through the book to reference Plato’s analogy of the cave, which I’d just naturally assumed he had. Another thing that became clear in discussion is that it’s a book everyone gets a great deal out of, and which things in particular connect up for you depends to some extent on what you bring to it—but everyone gets a great deal. Like I was getting Cyteen references and not getting The Matrix references, but other people were the other way around… what a terrific book. Read it and talk to your friends about it.

Secrets of the Sprakkar: Iceland’s Extraordinary Women and How They Are Changing the World — Eliza Reid (2022) Iceland is a lot closer to gender equality than anywhere else, how does that work? Very interesting book by Iceland’s “First Lady.” Reid is married to Iceland’s president, and an immigrant to Iceland from Canada. There are many interviews with people, most of them very interesting people, like Iceland’s women’s swim team, trans women, immigrants, parents, farmers, businesspeople… There’s a lot about childcare, which is the not-so-secret secret to real gender parity, and a bit about the women in the sagas. Iceland’s such an amazing place, with its geothermal electricity and frequent volcanic eruptions and, apparently, lots of support and no stigma for single parents. Reading this I kept coming across people saying about Iceland what I often say about Canada “It’s not perfect, but…”

The No-Show — Beth O’Leary (2022) This is a good, clever book. It was published as feel-good romance, but by my definition it’s women’s fiction. It’s also good enough, and clever enough, to be worth avoiding spoiling as far as possible while encouraging you to read it. The setup is that there’s one man, Joseph. He stands up three different women on Valentine’s Day, one for breakfast, one for lunch, and one for dinner. He doesn’t show up, he doesn’t text, he doesn’t call or answer calls or texts. What can possibly be going on? We have here the stories of three women and one man. Funny, compassionate, and one of our heroines is a woman lumberjack, but I’m not going to be saying “Oh yes, the one about the lumberjack” because this is genuinely good. I liked two other books by O’Leary, but I absolutely loved this one. Worth reading even if it means stepping outside your usual genre.

Penric and the Bandit — Lois McMaster Bujold (2024) Yes, I bought it on the release day and gobbled it up right away, why do you ask? Another Penric novella, with quite a lot of looking at Penric from outside, from the bandit’s point of view. Don’t start here, but a very satisfying new episode.

Hag-Seed — Margaret Atwood (2016) Re-read, book club. Retelling of The Tempest in the mode of Slings and Arrows and Jésus de Montréal. What a Canadian book this is! Felix is sacked from running the NOT!Stratford Shakespeare Festival and starts to do Shakespeare as a prison literacy project. Of course he’s Prospero, but the way the whole thing works out is surprising and delightful. This is also a deeply readable book that’s hard to put down once you start it. I only read it for the first time last October and was delighted to “complete my read” with this first re-read. I love a first re-read, where I know what the book is doing and can trust it not to mess things up and just lean in and enjoy it, but I don’t yet have the whole thing memorized. The rap sections are wonderful, Atwood is a marvellous poet, and both Caliban’s rap and the “Evil Bro Antonio” rap are highlights.

***Spoilers—another thing that makes this very Canadian is that Miranda is Felix’s dead child, and she grows up as a ghost, spirit, imaginary friend, in very much the way Anne’s child does in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne’s House of Dreams. Also, having Miranda dead and missed and beloved and also there but imaginary makes Felix much more sympathetic than Prospero, which helps. Highly recommended.

A Civil Contract — Georgette Heyer (1961) Re-read, started off as bath book but I found I didn’t want to stop reading it when I got out of the bath so I just read it. My favourite Heyer, mostly because it doesn’t have romance, but an arranged marriage and love and friendship. The economics of this are great, there are a lot of different characters, many of them typical Heyer types but done at their best here.

The Hundred Best English Poems — Adam Luke Gowans (1903) “Best” is a slippery word, and a hundred isn’t very many, and I kept second-guessing Mr Gowans’ choices. But it’s not a bad (free) collection of classic English poetry.

A Refiner’s Fire — Donna Leon (2024) I had this on pre-order and read it as soon as I had it. The new Brunetti, volume 33, and I suppose you could start here because all the books do stand alone. This is a series of detective stories about a policeman in Venice which Leon has been writing one a year for the last thirty-three years, and I hope she lives forever and writes a new one every year. There are ongoing characters. There are politics. There are weird artifacts of time in that Brunetti’s children were in high school thirty years ago and are in college now. But what there really is, what makes them worthwhile, is Venice and ethics. This one has an excellent helping of both. It makes me realise how little ethics one gets in a normal detective story.

The Story of Pisa — Janet Ross (1909) A history of Pisa, quite interesting, along with a guidebook to Pisa in 1909, which had rather more Byron and Shelley anecdotes than I’d have expected. Ross herself is an interesting person, a British woman who lived in Florence for decades in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and knew everyone. She was known to a whole lot of artists, art historians, and historians, as “Aunt Janet.” Her own work as a historian and translator is really valuable, but often undervalued because she came from outside the academy and did things like combine a history with a guidebook. The best place to start with Ross is Old Florence and Modern Tuscany rather than this, unless you’re particularly interested in Pisa.

The Shape of My Heart — Ann Aguirre (2014) Third in the teen romance trilogy about people who live in a particular dorm room. If this hadn’t had an entirely unnecessary Big Misunderstanding 70% of the way through on the dot, it would have been great. (It was both unnecessary in itself, and too easily got over if it had to happen. Bah.) Aguirre is very good at first person and getting me invested in characters in situations—this starts with being asked to go to a friend’s relative’s funeral as emotional support, which was gripping right away. Has anyone got Aguirre recommendations, bearing in mind I really don’t enjoy horror?

Parson’s Nine — Noel Streatfeild (1932) Re-read, but it had been so long I’d forgotten all the details. A beautiful woman marries a parson and has nine children in ten years, named after books of the Apocrypha. We see them as children and as they grow up and some of them die during WWI. Not exactly cheerful, and rather a lot of the usual Streatfeild children’s book elements but much darker.

Memory — K.J. Parker (2003) Third in the Poldarn series, and weakest, though I still enjoyed reading it. Some of what’s here contradicts things in the first book as if he hadn’t thought it through, or he had forgotten or didn’t care about details. I believe this may be my last previously unread Parker, and I’ll have to re-read or wait for more to come out. Well, he writes fast, and indeed, checking I just preordered “New K.J. Parker Novel #1” for March next year which is pretty amazing—is he writing them faster than he can think of titles?

Selected Letters of Alessandra Strozzi — Alessandra Strozzi (2023) Alessandra Strozzi’s husband was exiled in 1434, and when her sons grew up, they were in turn exiled. They were rich bankers, and Alessandra stayed in Florence (women were rarely exiled) and wrote letters to her sons, advising them to eat fennel for their health, wait until they could marry Florentine women, and work for getting their exile overturned. Meanwhile in Florence she’s worrying about servants and who their sisters can marry, and thanking them for sending her things. These are very human letters, with very human worries. Their letters to her have not been preserved, just her letters, so it’s one sided, but we can often tell what they’ve said from her responses. Really interesting. I love the way letters open a window into lives.

Derring-Do for Beginners — Victoria Goddard (2023) Re-read, book club. Third Canadian book in a row we read for book club, and while it may not show as much as Hag-Seed (though perhaps a little more than Exadelic), it’s still very Canadian. In fact, this would have been a good thing to recommend for my “books in which no bad things happen” post if it had existed at the time. Everyone is well intentioned, and yet, adventures are happening. An interesting thing I noticed while we were discussing this book is that it is in conversation with Don Quixote, all three characters have absorbed stories about how the world should work, and want it to work that way, and are living as if they’re in the world of stories. This is a beautifully written and described novel about interesting people who are all outsiders in the interesting places where they find themselves. And this is a fantasy world, but a fantasy world that seems relatively mundane to its inhabitants. Also contains three middle-aged professional women who are close friends and a support network for each other. Longing for a direct sequel. It’s in the same continuity as much of Goddard’s other work, but set much earlier, and does not have any prerequisites. If you’ve read other books you’ll recognise some of the characters, but it’ll be fine even if you don’t—for about half the book club this was their first venture into this universe and it worked fine.

Just One of the Guys — Kristan Higgins (2008) Disappointing romance novel about a woman who moves back to her hometown, and who loves a guy who sees her as a friend. There are no real obstacles, only fake ones. I’ve enjoyed other Higgins, but this one was a little lacklustre.

Tuscan Countess: The Life and Extraordinary Times of Matilda of Canossa — Michèle K. Spike (2004) So what’s wrong with this is that Spike decides what she wants to be true and just states it. It is possible that Pope Gregory VII and Matilda of Canossa had an affair, they were certainly friends, and he certainly gave her the title of “daughter of St Peter” which nobody else has ever had. But on the other hand, one of his big reforms was celibacy of the clergy. A biography of Matilda should certainly examine that question and come down on one side or the other. Spike doesn’t do that, she assumes it was a passionate physical affair and just leans into that. She does the same with some other things. And she takes a chronicle written at Matilda’s instigation but after Matilda’s death as if it’s first-hand evidence from Matilda herself. So on the whole, this book is as Dorothy Parker said, filling a much needed gap, or in other words standing in the place where a better biography of Matilda ought to be. Disappointing.

Black Heart, Ivory Bones — Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling (2000) Definitely the best one that I have read in this retold fairy tale series. There was hardly a dud here, and some very, very good stories. Wonderful Howard Waldrop. Incredible Susanna Clarke. Tanith Lee, Greg Costikyan, Jane Yolen, Brian Stableford—just terrific. This whole collection is top-notch. If you like retold fairytales at all, get this one. There are things here I’ll be thinking about for ages.

The Stretton Darknesse Mystery — Moray Dalton (1927) Cosy village mystery in which the victim couldn’t have deserved it more, and virtue is rewarded. Also, there is a ton of class stuff and attitudes and mores in post-WWI transition—a kiss still means an assumed engagement, but illegitimacy does not make someone a bad person. Delightful descriptions of people and places. Dalton is not a first-class Golden Age detective writer, but her works are new to me, and she was prolific, and “previously unread” is a virtue in this kind of book.

Selected Stories — Theodore Sturgeon (2000) My goodness Sturgeon was good. Some of these stories come too close to horror for me to like. But the amazing thing about reading this collection now is recognising just how good they are. The first story in the book, for instance, is at this point a total cliché, it’s a situation where the US has been nuked and has to decide not to retaliate and wipe out all life on the planet. But it’s so compellingly written that I couldn’t put it down, and it was written in 1948, when nobody but the US even had nukes. It was probably the first story examining this situation! There are a lot of classic stories here, most of which I’d read before but not for a long time. I think Sturgeon is one of those people we don’t rank as highly as he deserves at this point, because almost all of his good work was at short lengths, and we tend to valorize novels. So I think a lot of younger people haven’t read much Sturgeon, and really, his level of craft is astonishing. Pick some up when you have the chance. You could do a lot worse than this collection, or any random collection you find in the library.

Descent — Marko Kloos (2024) The fourth in Kloos’ Palladium Wars series, definitely do not start here, but if you’ve read the other three, definitely go on to this one. There’s a solar system with multiple habitable planets (some more habitable than others) that was settled a thousand years ago from Earth. And a decade ago there was a war in which Gretia tried to conquer the system and lost, and now the consequences of that are playing out. Kloos is very good on making the military side work. This book is very much a piece of middle—no answers, just some stuff happens. There will be more.