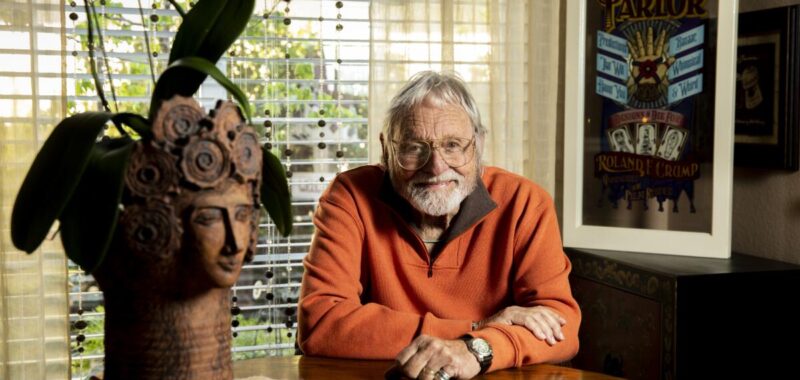

Rolly Crump had an outsized reputation. A rebel in the Disney fold. A beatnik. An unapologetic tell-it-like-it-is you-know-what.

Crump, who died last year at the age of 93, also forever changed the look of Disneyland. His art can be found in the Enchanted Tiki Room and, along with close friend and fellow artist Mary Blair, throughout It’s a Small World.

Crump’s style possessed a larger-than-life whimsy and circus-like loudness, and it caught the eye of Walt Disney, who plucked Crump from animation and one day assigned him what would become arguably the most recognizable clock in Southern California. The timepiece is the anchor of the façade of Disneyland’s It’s a Small World.

This week, an assortment of Crump’s lesser-known personal work will be on display at West Hollywood gallery Song-Word Art House. The show, dubbed “Crump’s The Lost Exhibition,” is curated by Rolly’s son, Christopher, who followed in his father’s footsteps to work for Walt Disney Imagineering, the division of the company responsible for theme park design. “The Lost Exhibition” will draw heavily on Crump’s late-1950s and early-1960s work, specifically his series of folk-house-inspired, rock ’n’ roll-style posters.

The event is open to the public Friday through Sunday, and the gallery is near the original location of one of Crump’s old hangs, folk club the Unicorn. A poster Crump drew for the venue will be a centerpiece of the exhibit. Christopher cites the freewheeling nature of the ’50s folk scene as a large influence on his father’s art, which had the sort of bold colors and intricate, line-heavy work one sees in a tattoo parlor.

Other posters show off Crump’s acidic yet silly sense of humor, such as what he called his “dopers,” that is, art that humorously celebrated drugs in the style of Beat generation barroom posters (“Be a man who dreams for himself,” reads a painting cheerleading opium).

Outside of his work at Disney, Crump continued to work on eccentric Pop art throughout his career. A comic strip-inspired 1967 poster for psychedelic rock group the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band belongs to the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. A print will be shown at Song-Word.

Crump stayed with Disney through 1970, although he would return multiple times before retiring in 1996. He also designed an attraction for Knott’s Berry Farm, briefly ran his own design firm and had a short-lived store, Crump’s, dedicated to his art. In 2017, Crump had a postcareer exhibition at the Oceanside Museum of Art, but Christopher sees “The Lost Exhibition” as a chance to explore his father’s lesser-known early work, before Crump would work on such attractions as the Haunted Mansion and It’s a Small World, the latter of which had its premiere at the 1964 World’s Fair.

“This is a personal thing for me,” Christopher says. “This is the exhibition that never happened. He should have done this. He should have had more gallery shows. The only real gallery stuff was when he had the Crump’s shop on Ventura Boulevard, but he never had a formal gallery show.”

Christopher, who will be on hand all three days to share tales about his father, spoke to The Times about the show. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your dad started working for the Walt Disney Co. in 1952. You were born in 1954. This exhibit places a particular emphasis on artwork from that era. When did you first become aware of your father’s work?

He was drawing all the time. He supported me as a model maker, and I had a desk and tools and he bought me kits. I started building models when I was 6 years old. I watched him draw. But later, I recognized that this huge body of work of his, he was doing all the time. He hung out with [animator-artist] Walter Peregoy a lot. Walter Peregoy would get up at 4 a.m. and draw and paint. And that started hitting me. Dad had two jobs — he was working in animation and he was working in construction on the weekends, and he was knocking out all this artwork and mobiles. When someone calls themselves an artist, they don’t have a choice. It is constant. It is all the time.

You have to also think about culture. Dad wasn’t changing diapers, cooking, cleaning and washing up and all that stuff. Men didn’t do that. It wasn’t like there was something wrong with him, but it wasn’t until later where it was like, “Hey, Dad, you have to help out with the chores.” Whatever the hell Dad wanted to do, he’d do it, so in Dad’s case, he would paint, draw, sculpt and make mobiles. He was going to keep satisfying that itch of having to do that stuff.

And everybody would help. My mom did a lot of painting on my dad’s stuff. He drew it, and said, “Paint that red. Paint that green.” I remember doing colors on paintings, and this was in the early to mid ’60s. We were all part of Dad’s little art machine.

In collecting this poster art, what impresses you today? What do you appreciate about the personal work he was doing while working in animation? I remember your dad saying he felt insecure as an animator.

These [animation] artists — Walter Peregoy, Dale Barnhart, Frank Armitage, and of course, Ward Kimball and Marc Davis — these guys were all amazing. Dad would say, “I knew how to use a pencil.” He could draw, but he had no formal education in the arts. These guys influenced him and he learned from them, but he needed to find his voice. I captured an interview recently — somebody sent it to me — of him giving a talk, and Dad told this great story about wanting to learn how to paint, to become an artist. He was trying to mimic Walt Peregoy’s style, and it wasn’t working. He was getting really frustrated.

He talked about going to an art show at the studio, and he saw a piece of a bunch of gargoyles sitting on a log flying kites. And the light bulb went off. He said, “I can do that.” Dad’s got a funky sense of humor, and the animation world was all about getting people to laugh, so he went home and he painted lobsters drinking martinis. And that was the first painting he did where he took the idea of telling a little story and making sure it was funny. That kick-started him.

What I’ve always loved about your father’s personal work is that there’s a free-flowing nature to it. You see that even in the poster for the Unicorn. It feels improvised, jazzy.

And what I think, and I’ve heard him say this, he was always looking for something different, and then to put some twist on it. When you think about the folk era, when it was really hot — burning hot — it was hobos on freighters writing songs about social injustice. These were “stick it to the man” people. All these things influenced him — the idea of folk music and freedom of expression.

Like, there was no way he could paint like those other guys. But he found his voice, and these posters became more satirical. It’s kind of mock advertising but very tongue-in-cheek. I’ll be playing a soundtrack of a lot of the music Dad had in his collection at home. So it’s a 4½-hour compilation of Miles Davis, Nina Simone, Peter, Paul and Mary, Quincy Jones, Harry Belafonte, Wes Montgomery — all the stuff we listened to the house or I heard in his Porsche listening to the jazz station.

How do you connect what we’ll see in this show with his best-known Disney work on It’s a Small World or the Enchanted Tiki Room?

Because he was drawing every day, his line work, his composition, his technical chops as an artist got better. That led to how he was able to come up with stuff in the Tiki Room, the toys in Small World. He didn’t wake up and roll out of bed one morning and become really good. There was a gradual development of who he was. Then he got to a confidence level. He knew who he was and he was unapologetic about it.

He started watching how Walt [Disney] behaved and he found his groove with Walt. He waited a few years before he really started becoming opinionated, and then once Walt started listening to him, it annoyed all the other Imagineers. They were all singing and dancing. “Whatever Walt wants.” Rolly wasn’t a dancer. How could this crazy beatnik character be Disney? It’s like musicians. It’s the chops. You mentioned the jazz thing — jazz is about improvisation. Jazz is about going with however the flow is going and following your crazy ideas. Walt believed in Dad’s crazy ideas.

And yet those crazy ideas helped define the tone of Disneyland. Modern theme parks are very much aligned with the look of film and television, yet there are multiple times, say, on It’s a Small World, where it’s very clear what Rolly’s influence was.

My wife didn’t know much about Disney. She rides It’s a Small World — and my dad had been doing birthday cards and Christmas cards — and she looked up at It’s a Small World and said, “Oh my God, it’s my father-in-law.” And that’s kind of my thought. This was all developed and worked out, and by the time the World’s Fair hit, and the ’60s hit, he had a good eight or nine years of messing around, and now he’s blossoming. Now he’s got a stage to work on.

So I’m talking about the ’50s and early ’60s before all that. What was it that happened to him that developed him and developed his confidence to be able to be that big-time guy?

It’d be like in music. He played a lot of little clubs before he hit the big stages. My vibe is to just kind of have people remember how artists become what they become.