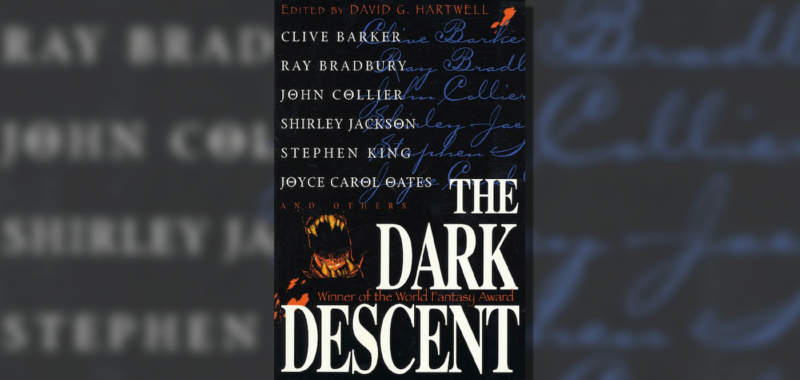

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Henry James is an author known for melding the gothic with an intense exploration of the psychological. In novels such as The Portrait of a Lady, this came with an examination of freedom and personal agency. In The Turn of the Screw (most recently adapted into the series The Haunting of Bly Manor, which also included an episode titled “The Jolly Corner”), James wove his modern psychological investigations into the framework of a gothic-horror ghost story, creating one of the most well-known horror novellas of the 20th century. “The Jolly Corner” is like those in many aspects, being a psychological investigation of a man’s choices. However, while James might follow his usual instincts, “The Jolly Corner” inverts the usual psychological aspects of the gothic, creating a portrait of a man who (through renewed purpose and focus) resolves his issues and banishes his ghosts instead of being consumed by them, concluding both James’ story and this second section of The Dark Descent on a resoundingly upbeat note.

Spencer Brydon is a somewhat idle but adventurous man who has spent most of his life touring Europe. After three decades, he comes back to New York to annoy his ever-patient friend Alice Staverton with his long, rambling conversations and check in on his real estate holdings back in America: his family home, which he calls his “Jolly Corner,” and the nearby renovation of an estate into an apartment building. Overseeing the yearlong renovation of the second property proves to be something Brydon has a talent for, both in terms of construction and management of real estate. Just as Brydon becomes preoccupied with the idea of what he could have been, had he taken a different path, a strange presence inserts itself into his life, taking the shape of the man he would have been if he’d stayed in New York. As Brydon’s spectral alter ego breezes through the halls of the Jolly Corner, a strange game of cat-and-mouse ensues, with Brydon hunting his alternate self through his childhood home and the attached building, driven to confront his double but afraid of what will happen when the two finally meet.

Brydon isn’t upset at his life not going the way he wanted—he’s somewhat content, though rather aimless and rambling. This sense is matched wonderfully in James’ use of paragraph-long sentences and constant asides in the first section, the discursive thickets of words mirroring the way Brydon himself thinks when he’s at a loss for things to do. Brydon has very clearly pursued certain things in life and found them wanting, and simply wonders what would have happened if he’d found more purpose and focus earlier in his life. It’s something everyone wonders about—how their lives would have gone if they’d just discovered what they wanted a little earlier. He’s not troubled or disturbed so much as he is just wistful and a little regretful about his time spent away from home.

This makes “The Jolly Corner” more comic than terrifying. Brydon isn’t someone who is seething with resentment or otherwise flawed or villainous; he’s just a man with a lot of unfinished business who somehow arrived at fifty-six because (to his mind) he was always looking out for the wrong things. With his long-suffering but patient friend and his housekeeper, he resembles a Wodehouse character more than any haunted Byronic hero found in gothic fiction. Which probably explains why the story, while tense, is more tonally and stylistically consistent with an adventure story than outright horror, ending happily with the hero fainting dead away at the sign of his double but waking up in the lap of Miss Staverton feeling revitalized, and even possibly finding love. Brydon resolves his psychological disturbance, there’s a bit of slapstick, and things end on an unambiguously happy note, with even the banter between Brydon and Alice pointing towards an optimistic future and away from his obsession.

Brydon comes alive while he hunts his doppelganger. Though it’s likely the action is meant to increase the tension, the first section of “The Jolly Corner” is languid and meandering by comparison. There’s more of a purpose, a drivenness to the way he stalks the halls, desperately hunting his double through the empty rooms of the vast house. He has, for the first time in the novelette, a goal—something to drive him towards and connect him to the world. He stalks through rooms, tries to avoid the traps he imagines his double set for him, and comes to enjoy the autumn evening streaming into the dark rooms and the strike of his cane against the marble floors. Brydon even establishes a routine, heading to hunt his double every night after hanging out at his social club. It may not be the most healthy (or subtle) search for closure, but the idea that he might reach it gives him a focus and purpose his otherwise idle life lacks.

Brydon’s search also gives him a reason to close this chapter of his life. His family’s home has remained empty after numerous tragedies, and he’s there to finally shepherd it on to its final form as a larger block of apartments. As he left New York with much unfinished business, it’s no surprise that his ghosts (often connected to unfinished business) take on a more tangible (if ephemeral) form in the guise of the alternate Brydon, the one who stayed with his family through hardship, “went into figures,” and made (in his and Alice’s estimation) “millions of dollars.” It isn’t worth it, and he can’t live the life he imagines he would have had if he’d never gone to Europe in the first place, but the constant nagging spectre of both his family and the person he could have been haunts him until he’s finally able to banish them. This renewed focus and purpose feeds into the rest of his life, giving him tremendous acumen and allowing him, finally, to resolve things and move on.

That focus and purpose saves Brydon from a life of fruitless wondering about what might have been as well as from whatever fate might have occurred at the hands of his doppelganger. “The Jolly Corner” ends with Brydon having resolved his psychological difficulties and ready to set off on a renewed course in life. “The Jolly Corner” also deconstructs all the gothic tales through which Hartwell’s guided us, up to this point in the book—it’s a ghost story without a definitive ghost, a psychological story where the hero is neither disturbed nor swallowed up by his own psychological concerns, ending both the story (and the second section of The Dark Descent) on an unambiguously happy note. It’s a moment that proves not all has to be bleak, and sometimes all we need is a little more purpose, direction, focus, and a bit of closure to find the peace of mind we’re chasing.

And now to turn it over to you—is “The Jolly Corner” a deconstruction of the usual gothic horror? Have you read The Turn of the Screw or seen Mike Flanagan’s version (or another adaptation)? And what would a P.G. Wodehouse ghost story look like?

After this, we’re off for the holidays, so be kind to each other, celebrate the solstice in whatever way you see fit, and please tell me what ghost stories you want to read over the break. See you in January for Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost,” as we begin the final section of The Dark Descent!