The expletives and biting one-liners that Eric Bieniemy unleashes on a football field never cut as deep as the internal dialogue.

If anyone is to blame for what goes wrong, it’s UCLA’s offensive coordinator, and he’s not afraid to let himself hear it.

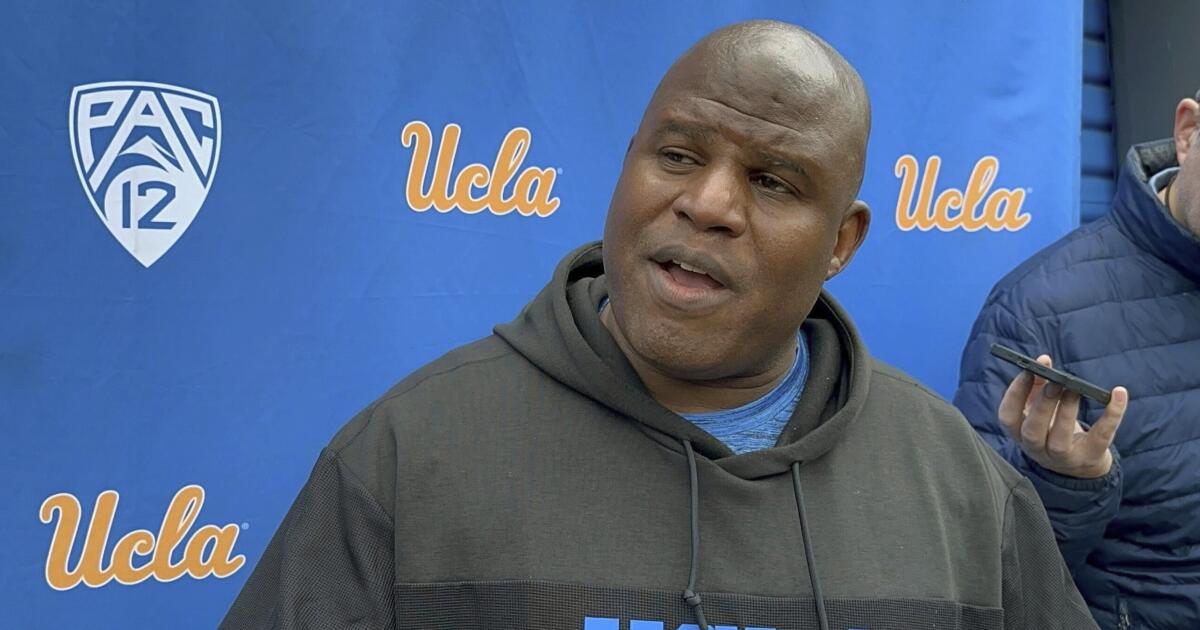

“You’ve got to understand, I go back and kick myself in the ass — man, ‘Why’d I call this play? Why did I do that? E.B., what are you doing?’” Bieniemy told The Times on Wednesday with a hearty chuckle.

“Just like I’m hard on them, I’m even harder on myself because it’s my job to make sure that I’m giving them the best opportunity. There’s a few calls that I know I would love to take back and if you could, if I had an opportunity to be a time traveler, certain things would be different.”

Things aren’t great for the Bruins two games into Bieniemy’s first season leading an offense that was supposed to be the team’s better half.

The veteran quarterback and running back have regressed. The wide receivers have been largely ignored. The offensive line has been pushed around.

Bieniemy’s West Coast offense has produced just one touchdown in each of UCLA’s first two games heading into a Saturday showdown between the Bruins (1-1) and No. 16 Louisiana State (2-1) at Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, La. UCLA is averaging 14.5 points, ranking No. 126 out of 133 major college teams.

It’s been a collective, and yet singular, mess.

“We’ve all just taken turns not doing our thing and so when that happens, I’ve always got to look internally, OK?” said Bieniemy, who is making $550,000 per year as part of a two-year contract that will also provide $550,000 in bonuses if he’s still employed through the end of July. “What can I do better to simplify it and make sure everybody has an understanding, and so I’m always over-analyzing self and making sure that I’m providing these guys the right information.”

Questions abound regarding the guru whose offense appears in need of guidance. Is Bieniemy’s NFL-style playbook too complex? Does his scheme rely too heavily on the pass? Are the Bruins prioritizing the wrong receivers?

Bieniemy pointed to the team’s strong practice performance and an impressive drive near the end of the first half against Indiana last weekend, when the Bruins drove 78 yards in nine plays for a touchdown, as evidence of this offense’s potential.

“When it’s all said and done, we just need to come out and play like we practice, you know?” Bieniemy said. “A part of that is getting our guys to understand, just relax and go play. It’s still a game, it’s one of the best team sports that there is, but it’s still a game and you have to enjoy what you do.”

Coach DeShaun Foster has pinned the offense’s problems on execution, saying a running game that produced only 96 yards against Indiana would have been fine if a 29-yard run by T.J. Harden in the third quarter had not been wiped out by a holding penalty.

But Harden has not resembled the player who was the team’s second-leading rusher a year ago, running for 28.5 yards per game. Garbers’ decline has been even more pronounced, the fifth-year senior completing only 54% of his passes for 409 yards with one touchdown and three interceptions — the last number matching his total from all of last season.

Players have conceded the plays are long and wordy, Garbers saying he had filled seven or eight notebooks with plays he repeatedly copied as part of his efforts to learn the system. A few days before the Bruins played Indiana, wide receiver J.Michael Sturdivant said teammates were headed to Garbers’ home that night to study the plays. Are struggles learning terminology part of the reason the Bruins often look lost on the field?

“I don’t think the verbiage is necessarily a part of the issue,” Bieniemy said. “It’s just making sure that we can go out and execute together as a unit, as one.”

In many ways, Bieniemy’s presence has been galvanizing. He arrived to a hero’s welcome six months ago, his new coworkers lining a hallway inside the practice facility to applaud his first day on the job. Wearing one of his Super Bowl rings, Bieniemy took it off so that Foster could have a closer look.

“It’s time,” Bieniemy said that March day, alluding to big plans for a program that hasn’t won a major bowl game in more than a quarter of a century. “It’s time.”

As part of that transformation, Bieniemy unfurled zing to go with the bling, mixing in a few choice words as part of his message.

After Garbers fumbled during one spring practice, Bieniemy barked, “Ethan, get your ass together and fix this … !”

When the offense wasn’t displaying the toughness he wanted, Bieniemy bellowed, “Put a hat on a … hat, let’s play ball!”

A false start triggered another Bieniemy barb. “If we can’t get the … snap count,” Bieniemy yelled, “your ass can’t play!”

Rather than cover their ears, players praised Bieniemy’s attentiveness and said he offered as much praise as criticism.

“He’s very loud, he will scream at you if you’re not doing the right thing,” Garbers said, “but he is your No. 1 fan when you do the right thing. He’s the perfect balance between your best friend and your coach.”

Bieniemy is the rare two-time Super Bowl champion with something to prove. The Washington Post reported earlier this year that Bieniemy had struck out in interviews with 15 NFL teams for head coaching vacancies, leading to questions about his qualifications and interpersonal skills. One longtime NFL figure familiar with Bieniemy, speaking on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter, said he came across “like a bull in a china shop; he’s almost honest to a fault, too.”

During a five-year run as the Kansas City Chiefs offensive coordinator, his collaboration with coach Andy Reid left some with the impression that Bieniemy remained an apprentice because he only called plays in select situations while helping the team win Super Bowls in 2020 and 2023.

“I just say, ‘Hey, what do you like here?’ ” Reid told The Athletic in 2020 while explaining instances in which Bieniemy would call plays. “And let him take it and go. We bounce it off each other.”

Ron Rivera gave Bieniemy a chance to go solo before last season, hiring him as the Washington Commanders offensive coordinator and assistant head coach. Among other things, Rivera told The Times, he was wowed by Bieniemy’s knowledge of the roster and plans for how he would best use everyone.

“He was very well prepared,” said Rivera, who coached the Commanders from 2020-23. “And then when you start talking concepts and ideas, you say, ‘Wow, this guy is really, really smart.’ I mean, he had a really good eye for the game and was very impressive as we went through the interview.”

The Commanders won their first two games before stumbling to a 4-13 finish. An offense that ranked No. 23 in the NFL in scoring was widely derided as too reliant on the passing game. Perhaps more troubling, Bieniemy reportedly clashed with players as a result of his abrasiveness. For better or worse, Bieniemy never played favorites.

“He doesn’t say, ‘OK, I’m going to treat this guy special because he’s a star and I’m going treat this other guy [differently] because he’s not a star,’ ” Rivera said, “he treated everybody the same and that’s kind of funny because some of the guys who were stars felt that they shouldn’t be talked to that way, but he talked to everybody that way and that was just him, that’s who he is.”

Taking a softer approach upon the start of his second stint at UCLA, where he had once been the running backs coach for three seasons under coach Karl Dorrell from 2003-05, Bieniemy dined with players before he yelled at them.

“I was always at the table with him and we weren’t even really talking about football, just talking about life, life questions, seeing where he came from because he’s a local guy too,” wide receiver Logan Loya said, referring to Bieniemy having moved from New Orleans to Hollywood when he was 10 years old and later starring at running back for Bishop Amat High, “so it’s cool to see that loop, so we did that multiple, multiple times.”

Bieniemy said it was his way of letting players know they could come and talk to him about anything — football or otherwise — to build rapport and connect on a human level. Foster has said that Bieniemy criticizes the performance, not the performer, a mantra that resonated with players.

“You know, a lot of people, a lot of critics, have a lot of things to say about him,” wide receiver Rico Flores Jr. said. “I say it’s the total opposite: You gotta learn Bieniemy, you gotta learn how he moves and operates, and he’s very respectful, at least to the players, I feel like.”

Indeed, Bieniemy’s booming voice sometimes carries encouragement across the practice field. After Harden broke off a nice run in the spring, Bieniemy shouted, “Good job! Good job!” On another occasion, players milling about nearby, Bieniemy told them, “Don’t be afraid of being great! It’s OK!”

Given the complexity of his system, greatness can take time. Rivera said he believed the Commanders could have succeeded if Bieniemy was given a second season to continue teaching his offense to a team with a young quarterback.

Watching from afar, Rivera said a similar timeline could be in play for the Bruins.

“If you say, ‘Hey, you’ve got one year to do this,’ man, that’s going to be hard,” Rivera said, “but if he gets time and the players can grow in this, I think they have a chance.”

Bieniemy doesn’t give up easily. As a running back at Colorado, he stuck it out for four years despite extreme homesickness and being called the n-word on an overwhelmingly white campus, finishing third in voting for the 1990 Heisman Trophy. As a running back in the NFL, he lasted nine seasons despite starting only one game. As an NFL assistant, he forged ahead despite repeatedly being passed over for head coaching jobs.

His new offense got off to a slow start? That’s nothing.

“It’s only Week 2, OK? It’s only Week 2,” said Bieniemy, who turned 55 in August. “These guys can accomplish any goal that they want to as long as they put their mind to it.”