When a dive center in a flooded quarry near Bristol, in the UK, was suddenly shut down in early 2022, many recreational scuba divers were left scratching their heads.

Almost two years later, they got some answers. DEEP, a UK-based ocean technology company that purchased the dive spot as a research hub and company campus, came out of stealth mode last September, revealing its mission to “make humans aquatic.”

The cornerstone of its plan is an underwater habitat called the Sentinel system, which it says will allow people to live and work at a depth of 200 meters (656 feet) for up to a month.

The Sentinel system is comprised of interconnected modules and can be used for purposes ranging from collecting data about the oceans’ chemistry to excavating historical shipwrecks. The scalable habitat can be configured in different shapes, making it as suitable for a six-person mission as a 50-person research station, according to DEEP.

The company hopes that its habitats can catalyze a permanent human presence underwater, like an International Space Station (ISS) – which, since 2000, has allowed humans to live and work in space – for the ocean.

Last week, DEEP announced a precursor to the Sentinel, a smaller underwater habitat which the company will use to develop systems for the Sentinel but will also be released as a separate product.

Vanguard, a 12-meter (40-feet) by 7.5-meter (25-feet) habitat with enough space for three people to stay underwater for up to a week, will be ready to go into the water at DEEP’s UK campus in early 2025.

The pilot habitat could have important uses when quick deployment is needed, like the search mission in August for survivors of a superyacht that sank off Sicily, Sean Wolpert, DEEP’s president, told CNN.

With the vessel sinking to a depth of 50 meters (164 feet) divers could only stay underwater for about 12 minutes before resurfacing. An underwater habitat placed on the seabed near the wreck could have served as a base for divers instead, said Wolpert.

Today, there is only one operational undersea research lab in the world, run by Florida International University, which is used by everyone from researchers studying corals to NASA astronauts undergoing extreme environment training. If all goes to plan, Sentinel will be ready to go by 2027, and Wolpert hopes to see them deployed in locations across the world. But DEEP acknowledges that it’ll take a major effort to reach its ambitious goals.

“Why hasn’t it been done before in the way we’re trying to do it?” asked Wolpert. “Because it’s very hard. So, we have been working tirelessly.”

“A catalyst for new careers”

Sentinel’s modules will be 3D-printed by a group of six robots, using steel reinforced with a nickel-based superalloy called Inconel, which can withstand extreme conditions and has been used in components for the Space Shuttle and SpaceX rockets.

Depending on what pressure it’s operating at, the Sentinel system can be accessed either by submarine, which locks with the habitat, or divers can enter via a “moon pool” opening at the bottom.

A support buoy on the surface will be equipped with a Starlink interface for connectivity, and the habitat will be powered with renewable sources like wind turbines and solar panels on the surface.

The company is pre-revenue but is engaged in advanced discussions with organizations and governments around the world, said Wolpert, who is a former hedge fund manager. Customers can lease, buy, or just share space in a habitat, depending on their needs..

The habitats, he added, could act as a catalyst for new careers and new investments related to the ocean, “very much like what the International Space Station did in terms of making space sexy again.”

Other uses might include monitoring and repairing critical subsea infrastructure, tourism, training for space, coral restoration, naval dive training, and medical research. When its job is done, the habitat can be redeployed in a new location.

DEEP’s work comes at a time of growing interest in utilizing the oceans’ resources – from offshore wind energy to deep sea minerals.

But the habitats could also allow marine biologists to get an understanding of the ocean not possible during shorter visits, via scuba diving or using submersible vessels.

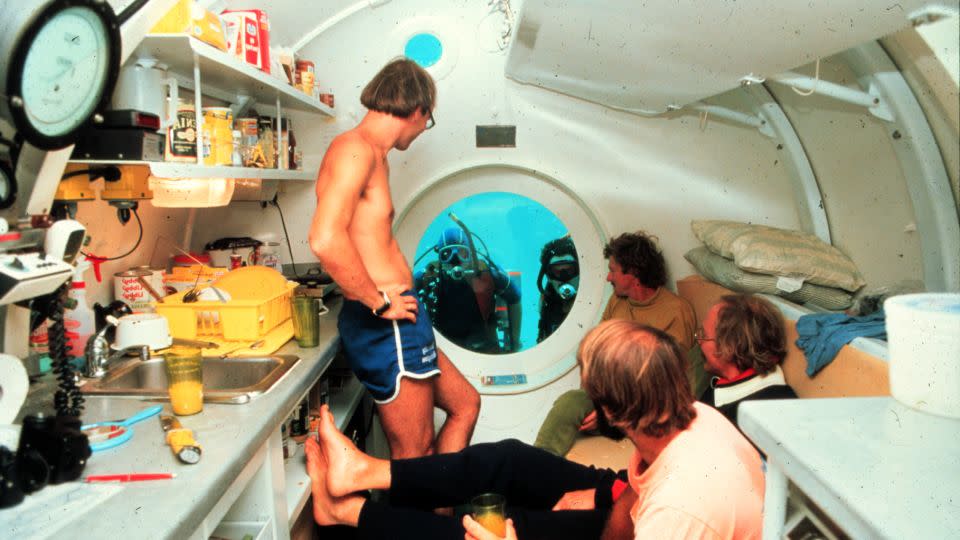

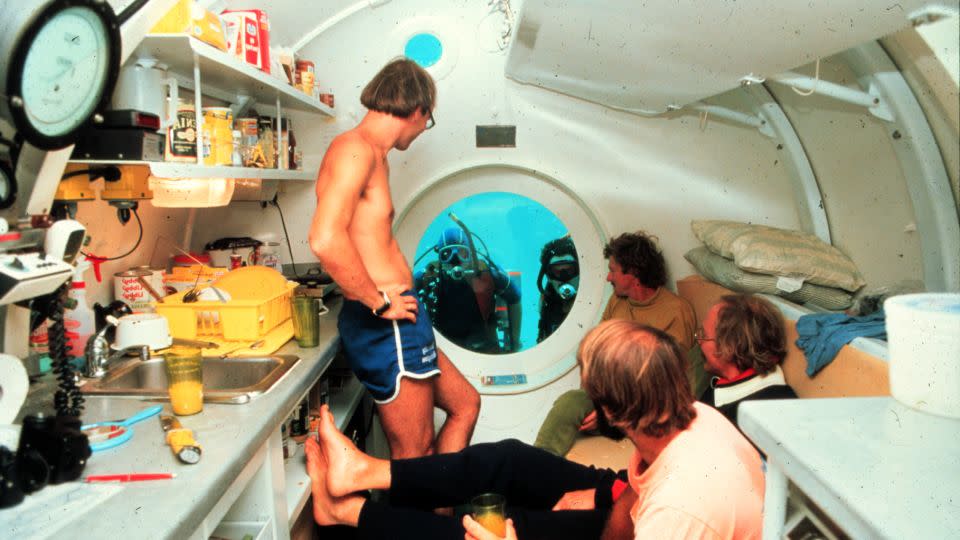

Bill Dennison, a professor of marine science at the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science, spent time studying seagrasses aboard Hydrolab, an early undersea research habitat active until 1985 in the US Virgin Islands. “I learned more about the ocean in that one week of my life than all the other thousands of dives I’ve done,” he said. “You just get a sense of the flow of life undersea.”

Still, he understands why there aren’t more subsea habitats. “They’re dangerous and expensive,” said Dennison. “You need a lot of up-to-date, good equipment, and you need up-to-date, qualified personnel.”

What gives DEEP a competitive advantage, according to Wolpert, is the support of its founder, who he won’t name besides saying he’s a “North American tech entrepreneur…who likes to be quite private,” and wanted to increase the understanding of the oceans, and their critical role for humanity.

Dennison, of the University of Maryland, said Hydrolab was damp, cramped, lacked indoor plumbing, and had only three beds for four occupants.

By contrast, Sentinel will feature soundproofed bunks, and a communal hall for eating and socializing. “It’s not going to be a Four Seasons suite, but when you leave, you’ll want to come back,” Wolpert said.

It may sound like a sci-fi fantasy, but some are impressed by the company’s progress. “They are assembling a very good group of people. This seems to be a well-informed undertaking,” Craig McLean, the former assistant administrator for research at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), who is not involved in DEEP’s work, told CNN.

The start of a new wave

Public interest in undersea habitats was first piqued by renowned French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, who in the 1960s sought to determine if “oceanauts” could live and work in the water. His missions to build “underwater villages” – dubbed Conshelf I, II and III – captured media attention amid the space race.

A series of other underwater habitats followed, but public interest in the oceans subsequently waned, said McLean, the former NOAA official.

NOAA operated Hydrolab, its first undersea lab, from 1970 to 1985. It deployed another, Aquarius, in 1988 in St. Croix, also in the US Virgin Islands. The habitat, which is slightly larger than a school bus, has six bunks and features a microwave, toilet, refrigerator, shower and internet access.

Today, it is located in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, where it remains the world’s only operational underwater lab dedicated to research.

But it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. McLean had to make the tough decision to transfer Aquarius’ operations from NOAA to the Miami-based Florida International University, which took over operations in 2013. “It’s unfortunately what I had to do based on the finances available,” said McLean. “Ocean investment by society has been underfunded.”

More recently, wealthy individuals have thrown their resources behind ocean exploration. OceanX, backed by hedge fund founder Ray Dalio, has brought subsea missions into living rooms via its media arm. Financier Victor Vescovo, the first human to travel to the deepest points in all five of Earth’s oceans, also captured his quests for television.

Initiatives like DEEP, and Proteus – an underwater observatory and research station announced in 2020 by the ocean tech company founded by Fabien Cousteau, the grandson of the legendary explorer – are likely to help drive more public interest and excitement in the oceans, McLean added.

Wolpert said that DEEP is more than a habitat, it’s also a platform for engaging the next generation. DEEP is working on a US Office of Naval Research-funded STEM outreach program, which will engage students in a series of habitat technology design challenges.

The company is also rolling out an institute and curriculum to train future Sentinel occupants. “If people can’t productively and safely use the habitats, they are just shiny objects that sit on the seabed,” said Wolpert.

He hopes DEEP’s holistic approach will help sustain the wave of interest in the oceans. “There’s a very large disconnect between the human race and the ocean,” said Wolpert. “Our goal is driving that generational shift and reconnecting humanity with the sea.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com