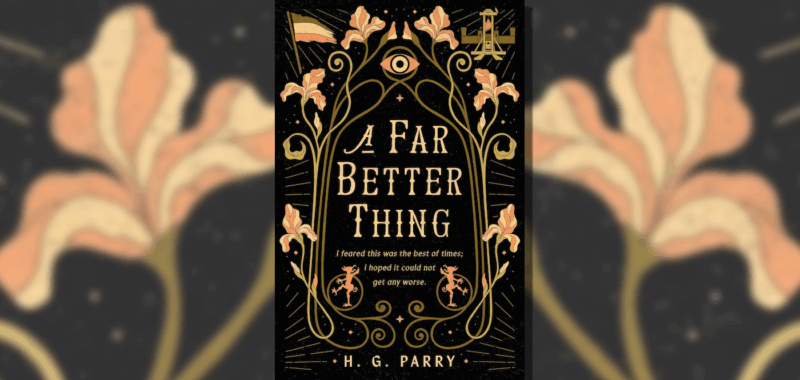

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from A Far Better Thing by H.G. Parry, a heart-rending fantasy of faery revenge set during the French Revolution—out from Tor Books on June 17th.

The faeries stole Sydney Carton as a child, and made him a mortal servant of the Faery Realm. Now, he has a rare opportunity for revenge against the fae and Charles Darnay, the changeling left in his stead.

It will take magic and cunning—cold iron and Realm silver—to hide his intentions from humans and fae and bring his plans to fruition.

Shuttling between London and Paris during the Reign of Terror, generations of violence-begetting-violence lead him to a heartbreaking choice in the shadow of the guillotine.

CHAPTER 1

IN WHICH I MEET MY CHANGELING

If you’re very fortunate, all a fairy will ask of you will be to steal a bone from a grave. They need them to grow buildings for the Children’s Quarter in the Realm. Wood, stone, trees—these things, even when brought from the mortal world, will shift with the rest of the Realm when planted into Realm soil. Mortal remains are the only things that stay fixed. It isn’t pleasant, the nightmares will be grotesque, you’ll need a very strong drink afterwards, but it will harm nobody. Depending on how you feel about the comfort of young children snatched from their cradles and raised among fairies, you might even say it will do good.

In Shropshire, when I was younger and new to the mortal world, I had no choice but to dig through the graveyards myself in the cold dark of night, shuddering with revulsion as my spade sifted the soil. In London, I was able to arrange things somewhat better. Early in my career I found Jerry Cruncher, who among other disreputable and reputable jobs moonlighted as a resurrectionist. He unearthed and sold corpses to medical students for study, and pocketed a few valuables on the side while he was about it. I surprised him one night as he bundled a corpse onto a cart. In exchange for my silence and a few coins now and then, Cruncher was very happy to bring me old bones from his excursions on request. It kept him out of trouble, and it kept me out of mouldering churchyards. I didn’t even need to drink on those nights, though usually I did anyway.

And so it was that in the very early hours of the morning I was to meet my changeling, I was leaning against the iron fence of a graveyard on the edge of London, waiting for a human bone. I didn’t know at the time that I was about to meet my changeling. I didn’t know about Addison Thorne, or Rosemary, or the revolution brewing in France; I didn’t even know about Shadow. I knew only that it was a black, windy night, and the rustle of grass and the whisper of trees overhead was like the protests of the dead. I drew my coat closer about me, and shivered.

“Hurry up!” I complained as Cruncher approached from the other side of the fence. “It’s freezing, it’s dark, and I still have work to look over for court tomorrow. What kept you?”

“Opportunities, sir, as it were,” Cruncher said cheerfully. Really, I had to admire him. Whatever his faults, which were many and ranged from extreme moral turpitude to lack of personal hygiene, he was relentless in pursuit of opportunity. If I had half his energy, my legal career would have been flourishing. “In the form of a freshly dug grave, not far from here. The students at the hospital like their corpses fresh. Excellent business.”

Buy the Book

A Far Better Thing

“I hope it didn’t delay you in the pursuit of my business. I told you, they need to be collected at the midnight hour. I may not be able to tell, but believe me, those who want them will.”

“And so they were.” Cruncher handed over a bundle wrapped in grimy cloth. I unwrapped it with fingers numbed by cold, and by the light of Cruncher’s lantern made out a pale gleam of a shinbone, the curve of a rib. They were very old, as I requested. Another point in Cruncher’s favour: he did what was asked, and asked no questions.

“I might be seeing you in that courtroom come daylight,” Cruncher said conversationally, as I wrapped the bones again. “The bank wants someone there to deliver messages. Mr. Lorry’s been called as witness for the prosecution.”

“I know.” Of course I did. It was my colleague who would question him, but it was my job to prepare the questions, and I had a good memory for witnesses. Besides, I knew Mr. Lorry: he worked as a clerk at Tellson’s Bank on Fleet Street, where Cruncher acted as a messenger and odd-job man during daylight hours. A small, fussy man of business who suffered from the unfortunate impediment of a kind heart, and who would have been horrified to know exactly how odd some of Cruncher’s jobs were. “Well. I suppose you won’t find the Old Bailey so very different from here. The light will be better, the draughts will be lesser, but otherwise a similar collection of flies and maggots come to feed on human death.”

“You’re in a cheerful mood, aren’t you?” Cruncher said. “I always like to see a hanging case. Brings the city together, and if they’re convicted you get some free entertainment up at Tyburn. And this one’s a treason case, in’t it? They might draw and quarter as well.”

“It’s my job to stop the prisoner being hanged, drawn, or quartered—though if we succeed, they’ll blame Stryver, not me, fortunately. I’d hate to be so unpopular.”

“Not unpopular with me, sir, if you stop the drawing and quartering. It’s hard in the law to spoil a man, in my opinion. It’s hard in it to kill him, but it’s even harder to spoil him.”

“No doubt. I suppose there’s not much call for bodies that have already undergone dissection, in your line of work.” I tucked the bundle into my coat. “Well. I’d best be getting home. Thank you, as always, for the terrifying reminder of the depravity of human nature, and for the human remains.”

“No bother at all.” Clearly, the potential for a forthcoming execution really had put Cruncher in good spirits, or perhaps it was the extra corpse he’d found. “I’ll see you at the Old Bailey tomorrow, Mr. Carton.”

It was the Year of Our Lord 1780. It was a cold, grey March morning; I was a cold, grey legal advocate, twenty-five years old and not yet dead. I feared this was the best of times; I hoped it could not get any worse.

* * *

As Cruncher observed, I was in a black mood at the graveyard, and the similarities I drew between that location and the Old Bailey were greatly exaggerated. My mood is rarely any lighter, so I stand by them. Here is another, more curious, similarity though: both are beautiful. Much as I complain about the city— and God knows it’s a filthy cesspit—I’m always comforted by the solidity of London, the weight of its towering architecture and green trees and stone-grey sky. The Old Bailey is, confusingly, a new building, rebuilt only five or six years earlier, yet already it has the same reassuring permanence. It’s a stately private fortress that towers over the street, its two wings extended like the arms of a judge begging the crowds to calm down and show some decorum. Pedestrians ebb and flow around it, waves around a great rock. For someone like me, who grew up in a realm that never stayed still one minute to the next, it feels like a promise that some things, at least, will go on forever.

I arrived there rather late that morning, weighed down by a load of papers and a concealed shinbone awaiting collection. The air of the courtroom was already thick with voices and excitement, sweat and heat. The audience had paid their money and been boxed into the public gallery behind and above the jury; the judge had taken his seat across the room. Stryver, at the table for the defendant, was looking uneasily at his pocket watch. I took some satisfaction from the frown that crumpled his florid face. It was petty of me, but I’d had a difficult night.

Stryver’s brow smoothed when he saw me, though relief made him rather more irritable than less. “You’re late.”

“For what?” I reminded him, reasonably. “It’s your trial. I’m not required to be here at all.”

“I require you to be here,” Stryver said, which was absolutely true. He looked me up and down. “Are you drunk?”

“I am about as drunk as you are personally acquainted with this case.” I shuffled the bundle of papers I’d brought—collectively, they represented about three nights’ work—and slid them across the table to Stryver. “In other words, not enough, but we’ll both have to make do. Here are your notes. Do you want me to read them for you too?”

Stryver gave me a pitying look, but made no further comment as he took them up and began, hastily, to skim the first page. He was secure again in his superiority, and had only minutes to learn what he was arguing.

In fact, the case was relatively simple. A young Frenchman of five-and-twenty, going by the almost-certainly-false name of Charles Darnay, stood accused of espionage. Allegedly, he had been conveying information regarding the position and preparation of His Majesty’s troops in America between England and France over the last five years. His accuser, an Englishman named John Barsad, had found compromising papers in his desk and turned him in for a reward, naming several others as witnesses: Cruncher’s boss, Mr. Lorry, for one; as well as an elderly doctor and his daughter. It was possible that this Darnay truly was a spy, but I doubted it. I had thoroughly investigated John Barsad, and he just so happened to owe Darnay money. The war with America was going badly—people were looking for someone to blame. A French spy was perfect. And a dead man couldn’t collect his debts.

“Your best chance is to discredit the accuser,” I said to Stryver, as he leafed through my handwriting. “Get the gallery to turn on him instead, and the judge might rule in your favour.”

“They’re saying he’s a patriot without stain.”

I snorted. “Believe me, he’s stained. The usual sordid colours of alehouses and gambling dens, and a few even darker. And he’s the only one who has any evidence on Darnay. Papers detailing English troop movements, supposedly found in Darnay’s desk.”

“Written in Darnay’s hand?”

“Of course not. But the prosecutor will no doubt argue this only means Darnay was artful in his precautions and therefore all the more obviously guilty.”

“Do you not think he did it?” Clearly that particular bite of sarcasm was sharp enough for even Stryver to feel. “Darnay?”

“I think he’ll hang for it, in this climate, which amounts to the same thing.”

“True enough.” Stryver set the pages down and sat up. “They’re bringing in the prisoner now.” The crowds knew it. The clamour was reaching fever pitch.

I had never met the prisoner, Stryver’s client. I’d prepared the brief, as junior advocate, but Stryver didn’t like me to visit the prisoners at Newgate, and I wouldn’t have even if he did. This was Stryver’s arena, and he was welcome to it. My work—the real work—had been done backstage. He would be praised, and I would be left alone, and that was how we each preferred it. My only task for the day was to endure the trial, nudging the flow of questions as much as needed. Then I would slip away to hand off the human bones in my possession, rejoin Stryver at his offices, and then finally, worn out by work and drink, I might be able to sleep. I didn’t care one eyeblink for what the prisoner looked like.

Until I glanced up, and I saw that he was my changeling.

I felt it before I saw it. My nerves twitched, and my flesh tingled as if at an encroaching storm. I was looking at myself. A far better version of me, of course: all changelings are more beautiful than the human beings they substitute, and in my case that wasn’t hard. The prisoner was well-grown and well-looking, and his dark hair was caught back neatly from a sun-browned face. My lifestyle was conducive to neither growth nor health, and under my lopsided wig my own hair hung limp and unkempt. My face was pale, and for that matter would charitably be called “bony” rather than the “sculptured” that the prisoner’s jawline and cheekbones invited. And my eyes are green-blue flecked with brown, as little like the dark, bottomless blue of a fairy replacement as a marsh is to a clear pool. But he was me. Myself as I could have been.

“Silence!” the judge called, and the ambient noise level settled to something below deafening. The courtroom came into focus around me again: the crowds buzzing like flies, the smell of perspiration and the herbs strewn about the place to combat gaol fever, the judge banging his gavel and calling the room to order. For all my shock, I barely missed a beat in settling back and tilting my head to look firmly and disinterestedly at the ceiling. Still, in that beat everything had changed.

My changeling. The replacement the fairies left behind when they took me, over twenty years ago, from my cradle. The man who had been living the life that should have been mine. Something was very, very wrong. We were never supposed to meet our changelings; we were never supposed to learn who we once were. Either there had been a very grave oversight in the Realm, or somebody was deliberately breaking the rules. Whichever it was, I would almost certainly have to pay for it.

There was no sense in worrying about that now. I was here; he was here; there was nothing that could be done about it. Even the fairies could make no move in such a crowd of people. All I could do was wait, endure, and look at him as little as possible. But knowing there was no sense in worrying never stopped anyone from doing so. Worse yet, I couldn’t stop wondering, as I hadn’t for years.

Charles Darnay. I doubted that was his real name, so it wouldn’t have been mine. I had no idea what his life had been before this, and so I could draw no real conclusions about that either. He was French. That meant I had been born in France—that I had been taken in France. I knew France. I had lived in Paris for a time as a student, studying law in the Latin Quarter. Had anything there seemed familiar to me? It must have done. How could some part of me not have remembered?

“Looks rather a lot like you, doesn’t he?” Stryver remarked in an undertone, as the attorney-general began his summary of the case. “Considering he’s a Frenchie. He’s not your long-lost brother or something?”

“Don’t be ridiculous.” My voice, I was relieved to hear, sounded perfectly normal. “You know I don’t have a brother.”

Excerpted from A Far Better Thing, copyright © 2025 by H.G. Parry.