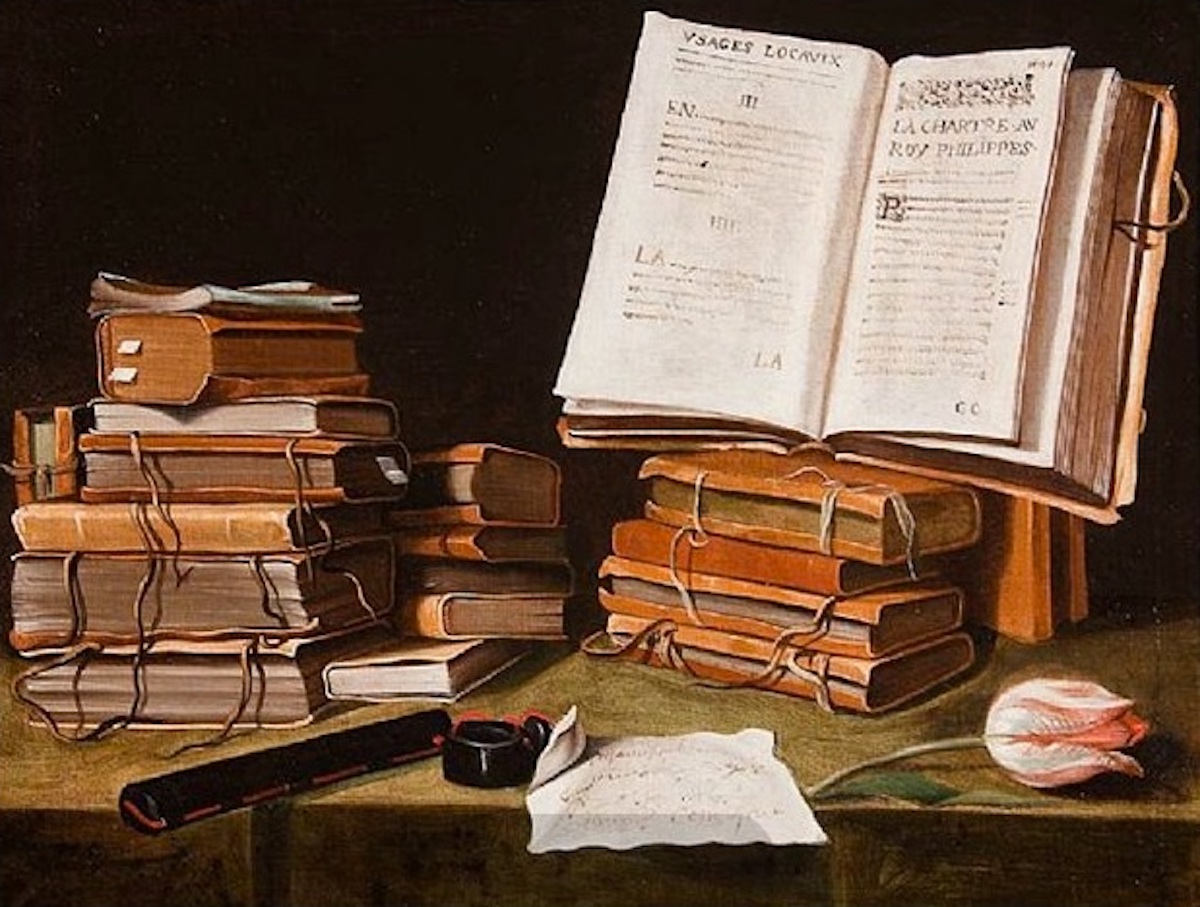

Yesterday, I finished reading Erin Morgenstern’s The Starless Sea for the second time this year, and it reminded me of something I’ve always loved—the way the physical form of a book shapes the experience of a story. The Starless Sea is a novel about the love of storytelling and books. Zachery, our main protagonist, finds himself lost in a world full of stories, a place known as The Starless Sea, a cavern-like refuge which is truly is a bookworm’s dream. Stacks of books, cosy wingback chairs and bumble bees to bake you biscuits as you have the time and space to just read. It made me consider how precious reading is. There’s something timeless about holding a novel in your hands, feeling the weight of its pages, and getting lost in its world. Many readers speak lovingly of the smell of a new book, the thrill of finding a floppy paperback at Waterstones, or the magic of discovering a sun-aged title hidden in the back of a second-hand shop. But beyond the tactile nostalgia, there is an art form here—one that is evolving in surprising ways.

With the rise of social media like BookTok and Bookstagram, readers are increasingly drawn to beautiful editions. These special titles have become an affordable luxury, especially important amid the cost-of-living crisis. Some of my favourites include the Folio Society edition of The Song of Achilles, Wuthering Heights from Chiltern Publishing and my beautiful edition of The Tainted Cup from Inkstone Books. But it’s not just about aesthetics. The book as an object, from its typeface, to its dimensions, plays a crucial role in how we experience stories.

Having worked in publishing for over a decade, I’ve witnessed firsthand the intricate process of transforming digital manuscripts into tangible books that live on readers’ shelves. Although I haven’t been directly involved in production, I’ve observed the meticulous attention given to every aspect of a book’s creation—from the jacket design to the choice of typeface, each element carefully selected to enhance the story’s impact. The choice of typeface is especially crucial, as it can subtly influence the mood and tone of a narrative. For example, when Natasha Pulley selected the Bell typeface for her novels, she wasn’t merely choosing a font; she was making a deliberate artistic decision. Bell, originally designed by Richard Austin in 1788 for John Bell’s The Oracle newspaper, evokes a sense of classical elegance and historical continuity, qualities that resonate deeply with Pulley’s intricate, time-spanning narratives.

Similarly, Anna Smaill’s use of the Doves typeface in her debut, The Chimes, carries profound historical significance. The Doves type was infamously lost to the Thames in 1913, thrown into the river by Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson amidst a bitter dispute with his business partner. Rediscovered in 2015 after nearly a century submerged, the Doves typeface has come to symbolise a resurrection of forgotten art, mirroring the themes of memory and loss that Smaill explores in her novel.

The physical form of a book is more than just its packaging; it’s integral to the story it conveys. In a world increasingly dominated by digital media, this aspect of storytelling deserves celebration. Books transcend mere narratives—they offer comfort and refuge.

My connection to literature took root at fourteen, during my first experience away at boarding school. Homesick and yearning for the familiar, I found solace in the volumes I had brought with me: Prince Caspian, A Little Princess, and Tom’s Midnight Garden. These stories, gifted from my grandmother’s library, served as a bridge to home. My Grandmother is a formidable woman—reminiscent of Maggie Smith’s character in Downton Abbey—who instilled in me the importance of treating books with respect. She encouraged my curiosity, allowing me to explore the library while teaching me to be gentle and mindful with each cherished volume. Our shared love for literature has always forged a bond between us, and I have many cherished memories of us reading together in her garden. A Little Princess, in particular, resonated deeply, as I identified with Sara Crewe, a girl navigating loneliness but ultimately rewarded for her kindness and resilience, much like many Victorian heroes that my Grandmother and I read together.

This led me to see books as more than just objects; they carry the marks of our experiences. As David Mitchell once said, “A book you finish reading is not the same book it was before you read it.” He was referring to the transformation that happens within us when we finish a story, but for me, this also speaks to how books themselves change in the act of being read.

My mother is constantly urging me to sort through my overflowing collection of books, and she’s right—I don’t have enough space in my London flat for the number of books I own. But, as we all know, book buying and book reading are entirely separate hobbies. This shift towards beautiful, ‘affordable luxury’ editions is a smart move by publishers—since lockdown, we’ve seen a rise in physical book sales, and last year, the number of independent bookshops in the UK increased for the sixth consecutive year. Communities like BookTube, BookTok, and Bookstagram have played a significant role in bringing physical books back into the mainstream. In particular, genres like romantasy and book subscription boxes have fueled this resurgence, and for some readers, owning multiple editions of the same book has become a rite of passage. Whenever I visit friends, I always check their bookshelves first because they tell me so much about who they are and what they love. Despite working in publishing and knowing the ins and outs of the industry, I am an unabashed buyer of beautiful books. I own three copies of In Memoriam by Alice Winn and have been easily persuaded to buy multiple editions of Babel because they are simply gorgeous. I regularly check Goldsboro Books for their latest special editions and love that they only sell signed first print.

However, I can’t ignore the real challenges that come with overconsumption and rising prices. Like many readers, I find myself struggling with space and can’t justify owning multiple copies of the same book, no matter how beautiful they are. As hardbacks climb to around £20, it becomes a luxury to consider their format, and sometimes, the aesthetics alone can’t justify the expense.

Some publishers now prefer print paperbacks with French flaps and foil-stamped jackets to justify the £14.99 price point, moving away from the traditional hardback as the first print run. Is this a sign that hardbacks might become less common in the future? We’ve already seen genres like Romance and Crime adopt paperback originals, and I wouldn’t be surprised if historical fiction follows suit. While book subscription boxes might keep hardcovers alive for genres like science fiction and fantasy, the price tag is likely to keep rising.

Are e-books the ultimate solution for storytelling? My Kindle mostly serves as a tool for work-related reading, but I completely understand why many people prefer it. The convenience of carrying thousands of books in one device is incredibly appealing, especially when space is limited. For readers with dyslexia, like myself, the ability to customize fonts can make reading more accessible and enjoyable. And audiobooks hold a special place in my heart. My brother, who is blind, relies on audiobooks to immerse himself in the joy of storytelling. Witnessing his deep appreciation for this format highlights the diverse ways we connect with literature. Each Christmas, we engage in lengthy discussions about the books we’ve been reading, providing a cherished opportunity for my very British family to bond. He shares which narrators he’s enjoyed, discussing the voices that brought stories to life and those that didn’t quite capture the essence he hoped for. Knowing that audiobooks now account for nearly 12% of the UK’s book sales reassures me that this format will continue to grow, making books more accessible and offering new opportunities for publishers. While I deeply appreciate the tactile joy of physical novels and their significance in my life, I also recognise the benefits of digital formats. After all, though the story itself is central, the format through which we experience it profoundly shapes our connection to it.

Few novels have buried themselves into my soul like The Wode Series by J Tullos Hennig, Amberlough by Lara Elena Donnelly and anything written by Natasha Pulley. Yet even among these beloved books, my most prized possession—the one thing I would risk running back into a burning building to save—is my copy of The Song of Achilles.

My battered and bruised copy was purchased in 2012 on the night it won the Orange Book Prize (now the Women’s Prize for Fiction). At seventeen, I found myself in the audience at the ceremony, captivated as Miller read an extract—specifically the moment when Patroclus first catches sight of Golden Achilles, “his heels flashing pink as licking tongues.” In that instant, I felt profoundly seen by Miller’s words, resonating with the boy experiencing desire and jealousy toward someone destined for greatness. I was enamoured by Miller’s intellect and her ability to make the Iliad and Odyssey—texts I had only dabbled with at school—accessible and wonderfully queer. This queerness echoed the feelings I had long suspected within myself but had been too afraid to acknowledge in school. From that moment, I was smitten. As I prepared to attend university in Vermont, this book dug itself deep into my soul, inspiring me to change my degree to include a minor in classical literature. During J-Term, I even took Ancient Greek, just in case I ever encountered the original text.

It has been my steadfast companion for more than a decade, travelling with me through the pivotal moments of my life. This book carried me through university in a foreign country and accompanied me as I explored the U.S., dragging it across San Francisco and the West Coast. A deep black mark stretches across the bottom from the time my suitcase burst open, and I unwittingly pulled it along the pavement for over a mile before a kind stranger informed me I was about to lose it. It has been read to reluctant strangers on long coach journeys, and on romantic evenings in Italy. It was with me during my inter-railing trip across Europe and while island-hopping in Greece.

This book even helped me land my first job at Penguin Random House, where I wrote an essay on the importance of Greek retellings for my internship. Over the years, I’ve annotated it in sparkly pink pen, tabbed my favourite quotes, and even accidentally put it through the washing machine. It’s now on the verge of collapse, but it is a truly loved book. I’ll never forget the look Madeline Miller gave me when I handed her my dog-eared, battered copy of The Song of Achilles at The British Library just before the pandemic. Her raised eyebrow spoke volumes. This encounter took place in 2017, long before TikTok fame and even before the release of Circe. I can’t recall who Miller was speaking with; all I remember is the incredibly long queue and the excitement bubbling within me as I counted down the number of people ahead. As always, I attempted to express my appreciation for her work, but I think I only managed to mumble that it was a pleasure to meet her before I hurried away, a whirlwind of nerves and admiration.

In essence, I hope that all forms of storytelling remain accessible and cherished. Bookshops and libraries must always serve as safe third spaces, a place where everyone has the option to become Zachery finding their way to the Starless Sea. As Oliver Darkshire once said, ‘Anyone worth knowing enjoys spending time in a bookshop,’ and these spaces, filled with stories, should be celebrated. The romance of paper and ink, sun-bleached pages, and worn bindings deserves to be cherished. We should continue to expect and demand beautiful endpapers and marbled boards. Imprint yourself onto the pages of beloved paperbacks, highlight paragraphs, and leave your mark. These stories will carry a piece of you long after the final page is turned. Books are not meant to remain pristine; they are living objects meant to be handled, read, and loved. So, dog-ear that paperback, gently break the spine of a hardback, and leave your fingerprint smudges from the bath. Show each novel the joy of being read, and let it absorb its own story through your hands.